This is essential reading. Frequently, the reason a non-fiction book really grabs my attention is that it relates its thesis convincingly while still managing some how to read like a novel, with fully-formed characters and good pacing. I’m thinking, for example, of Lawrence Wright’s The Looming Tower, which is an absolute masterpiece of journalism on the origins of al-Qaeda, thoroughly sourced and replete with facts, but still as compelling as any thriller. David Grann’s The Lost City of Z, about Percy Fawcett’s ill-fated expedition into the Amazon, is another book with these traits.

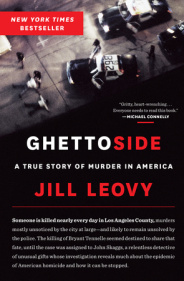

Ghettoside is not like either of those books. It’s certainly well-researched and it’s a page-turner in its own way, but the experience of reading it is nothing like the experience of reading a novel. It’s much more like reading a really good, really long newspaper article — which makes sense, because its author was formerly a reporter at The Los Angeles Times. The writing in Ghettoside is fine, but that’s not why you read it, just like that’s not why you read a newspaper article. You read it because the story it tells is important.

Leovy minces no words in letting you know what this book is about:

This is a book about a very simple idea: where the criminal justice system fails to respond vigorously to violent injury and death, homicide becomes endemic.

African Americans have suffered from just such a lack of effective justice, and this, more than anything, is the reason for the nation’s long-standing plague of black homicides.

Leovy packages her thesis and the supporting evidence for it into a narrative about a single murder in South Los Angeles. A young black man wearing a baseball cap also worn by members of a local gang is shot and killed by members of a rival gang.

This is not unusual: Someone is murdered almost every single day in Los Angeles, and more than half of the time the perpetrators of those crimes are never brought to justice. The reasons for this are many, and they include police indifference to crimes that appear to be gang-related; societal indifference to black-on-black violence (which dates back to the very beginning of this country, Leovy notes); lack of resources allocated to the detectives who investigate the crimes; community mistrust of the police (witnesses are often not willing to speak or don’t believe the police can protect them from reprisals if they do speak); and a historical lack of law enforcement in their neighborhoods that has led to a system of vigilante justice in which victims’ friends and relatives may prefer to get revenge on their own rather than rely on the police to find and arrest the murderers.

The book follows the investigation of this murder, placed in the hands of a detective who the cover of the book says has “unusual gifts.” What’s striking when you actually read it though is that in fact he doesn’t have any gifts that are particularly unusual. He’s relatively intelligent; he pays attention to detail. But those are traits shared by any good detective, I would assume. Really, the chief virtue of Detective John Skaggs is just his tenacity. He doesn’t give up. When witnesses won’t talk one day, he goes back to their house the next day. If they still won’t talk he shows back up that night. He knocks on doors; he bangs on windows. He doesn’t give up until people hand over the information he’s looking for. And one of the saddest parts of this whole book is: That’s all it really takes.

To bring to justice many of the murderers of young black men in this country, Leovy’s story seems to suggest, all someone would really have to do is try. And yet most of the time, those murderers remain free. Because, I guess, not enough people care enough to make it worth going and finding them.

In fact the murder that serves as the case study in this book, like many of the other murders Leovy describes for illustrative purposes, is never really a mystery to anyone but the police. The constant refrain that Skaggs and other detectives hear on the street in their murder investigations is, “Everybody know.” As in, everybody knows who did it. With few exceptions, though, most witnesses are unwilling to be the “snitch” who turns in the murderer, either because they know that the police can’t protect them from reprisals or because they believe that even if they cooperate, the police will never bother to actually close the case and arrest the killer. These beliefs aren’t the products of paranoia, they are derived from learned cultural experience. California — and, very probably, most other states — offers very few resources for the protection of witnesses, and what it does offer is not particularly suited for the needs of the very poor residents of these communities, for whom their neighborhoods offer the only semblance of safety and stability they will ever know.

Sometimes Leovy will interrupt the narrative and note that at that moment, or within a few hours of that moment, a few blocks or a few miles away, someone else was murdered and she’ll name him and briefly tell his story. Then she’ll continue: That night, yet another person is murdered, with his or her story. The next morning, someone else. Two days later, someone else. And she’ll keep going, the stories running on for pages, until you get the sense that she could just keep going in an unbroken line from that moment to the present, right now, as you sit reading the book, that there have been enough murders for her never to have to stop. Because there have been that many murders, and she could keep going.

Leovy points out at one point that in the early 90s when this violence was at its worst, the per-capita violent death rate of black men in their 20s was almost exactly the same as it was for American soldiers deployed to Iraq following the 2003 invasion. The homicide rate has declined since then, but it is still shockingly high and black men remain significantly more likely to be murdered than whites of any age or income level.

Racism, civil rights, all the issues and problems caught up in those terms, they’re not easy and simple things to solve and I, certainly, don’t pretend to be smart enough or experienced enough to have anything very meaningful to say on how the big problems should be addressed. Leovy doesn’t either. She points to just one problem — the rate at which young black men in America are being murdered with impunity — and one means of beginning to solve it. That way is, more or less, people really just need to start to care. This is a good book.