After reading a series of books that weren’t quite good enough to make the cut on this blog, I’m finally back with an update – and it’s not one, but two novels this time. They’re both mysteries, as I’ve been on a bit of a kick lately. I like mysteries, but I only like them when they’re fair – that is, when the reader has the opportunity to solve the crime along with the protagonist. That means, in my mind, that all the clues must be available for the reader to examine, with no last-minute revelations that the detective has all along had in his possession some crucial and hitherto unknown piece of the puzzle.

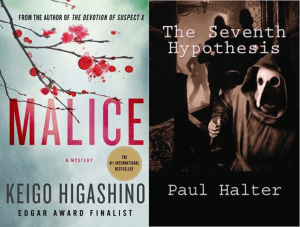

The first is called Malice, by Japanese author Keigo Higashino. Higashino, apparently quite well-known among mystery lovers, was a totally new author to me.

The novel is about an acclaimed author who turns up dead, having been murdered in his house shortly before he is to move to Canada. Suspicion quickly falls on the author’s best friend, who is himself an author of children’s literature. I won’t say who the guilty party is – but it’s not a spoiler, I think, to tell you that in this novel the mystery has less to do with whodunit than with why it was done. Higashino cleverly wraps the killer’s true motivation in layers of red herrings and incomplete explanations.

This novel does not quite follow the structure that I said I like – there are, in fact, some clues that are not available to the reader from the outset. However, the most important ones are all explicitly laid out well prior to the time the solution is revealed. I don’t know if a reader would be able to completely figure out the killer’s motivation prior to the time they are revealed, but an observant person could probably get pretty close to the actual solution, so I’m giving it a pass.

It earns that pass, in any case, because it is such a pleasure to read. The writing is spare, precise, and not at all showy. Higashino is not out to dazzle you with his literary prowess; he’s just telling a story. Nonetheless, some of the images from the book will stick with you long after you finish the novel. I’m reminded of Ernest Hemingway’s “Iceberg theory” of writing, the idea that writers can strengthen their story by leaving things out of it. As you read Malice, a pretty simple mystery story, you can sense things about the relationships between the characters, personal anxieties, and even things about Japanese culture and its changes, hardly any of which are ever explicitly brought up.

Another pleasure in Malice is the way the narrative flows – the prime suspect and the lead detective take turns narrating, each delving deeper into puzzle as he reacts to what the other has revealed. I saw someone online described the act of reading the book as akin to watching a tennis match, but I don’t think that’s quite right: Despite the apparent opposing ends of each character, the narrative is really a cooperative work. The detective and the suspect are, in spite of themselves, partners.

So that’s Malice. Read it, if you want!

The second mystery novel I read is called The Seventh Hypothesis. It’s by Paul Halter, a French novelist, but the story is set in late-1930s London. Unlike with Malice, I don’t really want to spend a lot of time on the writing. The pleasure of reading this novel is almost entirely in trying to solve the puzzle – and it’s an incredible, almost ridiculous puzzle.

The central crime in the novel would seem to be an impossible one: A musician is abducted by a trio of men dressed as 13th century plague doctors. They tell witnesses to the abduction that he has the plague, and they are taking him to the hospital. Later, a police officer comes upon one of those doctors standing over a trash can, muttering about a dead body. The police officer stops the doctor and looks in the trash can, but the bin is empty. Thinking the man crazy, he lets him go. After the man has left, the police officer looks again, and now there really is a dead body!

If this doesn’t sound insane enough, keep reading. The people who come to be the two suspects in the novel each have what appear to be ironclad alibis, supported by multiple witnesses who have no reason to lie. The dead bodies don’t stop coming, either, and each time both of the suspects has a clear motive for the murder but also a clear alibi that proves he couldn’t have committed the crime. Or does it?

The craziest thing about this novel is that it utterly adheres to the model of my favorite kind of mystery – the reader gets every clue along with the detectives, and the whole thing is completely solvable. There’s nothing supernatural in the explanation; everything makes sense once it’s all laid out. Watching Halter write himself into such a corner and then skillfully write himself back out of it was an absolute pleasure.

I should acknowledge, I guess, that there’s not much suspense in this novel. The crimes are so implausible, and the villains so villainous, that you can’t really believe anything that is happening – some of hte explanations are so labyrinthine (but, as I keep emphasizing, never unfair) that you almost have to laugh. It’s better to approach The Seventh Hypothesis less as a reading experience and more as if you’re simply trying your hand at solving a very ingenious puzzle.