No sooner had I published my own thoughts on Go Set a Watchman than I stumbled across this very smart Jezebel piece making a convincing argument that my understanding of the book, and of its predecessor, is completely wrong.

Uncategorized

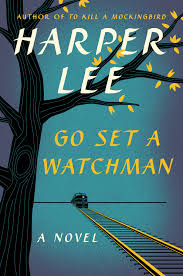

Go Set a Watchman, by Harper Lee

Go Set a Watchman is not a sequel. Why it is so difficult for people to understand this is completely beyond me. Part of the problem, no doubt, has to do with the way the book has been marketed. The book’s publisher has not been as forthright as I believe would be responsible about the novel’s provenance. Watchman is an early draft, a discarded draft, of a novel that was substantially revised and edited and eventually morphed into the classic we all know as To Kill a Mockingbird. Watchman was written first, then tossed aside, and never really intended for publication.

None of this is to say, however, that it’s not worth reading. All I mean is that if you try to read it as a sequel, you will be disregarding its author’s intent and also robbing yourself of any chance of enjoying the book for what it truly is – a fascinating insight into the creation of one of America’s greatest works of fiction.

Station Eleven, by Emily St. John Mandel

Station Eleven is, to some extent, about what it’s like to have survived after the end of the world. Even more so, though, it’s about how amazing it is to live in the world as we currently know it: a world where iPhones light up with messages from loved ones thousands of miles away, and we can respond to those loved ones instantaneously with a few taps of our fingers. It’s about the relationships we form and how they can develop and maybe fade away, and the lasting effect people can have on us – even those old friends whose emails we’ve long since stopped responding to.

Yes, the novel is set in a sort of dystopian future, a North America following a flu pandemic that has wiped out most of humanity and forced those who remain into a daily struggle for survival. These scenes are crafted as stirringly as anything else you’re likely to have ever read in any sort of dystopian novel. But it’s also about the fact, to quote the motto of the book’s group of protagonists (who are themselves quoting a line from an episode of Star Trek: Voyager) that “survival is insufficient.” The Traveling Symphony, as this band of wanderers calls themselves, is a group of musicians and actors that travels the ruined world giving performances of concerts and Shakespeare plays. Things take a dark turn, however, when they encounter a crazed “prophet” in one of the towns they pass through, and afterward begin disappearing, one by one.

The plot is not bad, for what it is, but it’s the least interesting part of Station Eleven. What keeps you reading are the bonds you develop with the characters, the way you come to share their sense of amazement at having had the opportunity to live in the world before the flu – the world we live in right now. It’s a pretty amazing place! That’s an easy thing to forget. I’m certainly guilty of taking the many miracles and conveniences of daily life for granted. This book makes you stop doing that.

Moby Dick, by Herman Melville

After reading The Art of Fielding, I felt compelled to re-read Moby Dick. It had been quite a few years since I read it last, so I’d forgotten a lot. One of the main things people complain about when it comes to this book are the supposedly endless descriptions of whales and the technical details of whaling. There is, in fact, a lot of that, but not as much as I had remembered there being. And some of it is pretty interesting, though plenty of times it does seem to drag on.

But another thing the book has a lot of, and that you hardly ever hear anyone giving it credit for, is a sense of humor that was far ahead of its time. Take a look at this passage, which is from the very first page of the novel:

The Art of Fielding, by Chad Harbach

The Art of Fielding is such a fun book. It’s about baseball, and the enjoyment of reading it is very similar in feeling to the enjoyment of going to a baseball game. There’s drama and suspense and you learn things about characters that you come to care about. Sometimes things can take a somewhat dark turn, but nothing ever gets too too bad and most of the time when you put the book down for the night, you’re going to bed happy rather than stressed out.

The First Collection of Criticism By A Living Female Rock Critic, by Jessica Hopper

Purely by virtue of its title, which is great, I knew almost from the beginning that this book would get an entry here. The book consists of essays that the author has written for Pitchfork and other publications over the years, and while some of them are much better than others, nearly all of them are at least worth the read. Her interview with the reporter responsible for unearthing the R. Kelly sexual abuse allegations, for example, is a particularly compelling.

My taste in music is not very broad or very deep, I’m ashamed to admit. I can probably list the number of artists I really love on one hand, and the total number of artists I follow on two. Maybe, if I were really stretching to come up with names, I might have to kick off a shoe. So a book of rock criticism – I don’t listen to much real rock, Bruce Springsteen being about as close as I get – would ordinarily not be likely to catch my attention. But that title: It’s just so good.

Kafka on the Shore, by Haruki Murakami

So I wrote all these blog posts a while ago

And I was going to wait until I had like a critical mass of books that I’d written posts about before launching this thing, but I decided that was stupid so now I’m just publishing the completed things I’ve written and then I’ll publish the others as I finish them. No one’s reading this at the moment anyway!

When We Were Orphans, by Kazuo Ishiguro

I am a big fan of this author. The Remains of the Day is one of my favorite books ever, and I also really enjoyed Never Let Me Go. One thing I like about Ishiguro, among many, is that he doesn’t ever write the same novel twice. RotD is about an English butler looking back on his life near the end of his career; NLMG is kind of a sci-fi novel about a group of clones who exist so that their organs can eventually be harvested; and I’m very excited for Ishiguro’s upcoming novel, The Buried Giant, which is a fantasy novel set in Arthurian England (UPDATE: This novel is out now, and I’ve read it and liked it a lot but haven’t written about it yet).

When We Were Orphans, meanwhile, is sort of a detective novel in the same way that NLMG was sort of a sci-fi novel. What I mean is that while the novel is about a detective, and contains many of the element of a typical detective novel, the various cases the main character solves or fails to solve are mentioned only in passing. Even the driving mystery of the story — the disappearance of the protagonist’s parents — goes without the usual treatment, and its ultimate solution is drawn only in broad strokes and without offering the reader much of the satisfaction of having arrived at the truth.

The Martian, by Andy Weir

This book is kind of like Cast Away, only on Mars and much funnier. Funny books can be tricky because it’s often the case that the more they make you laugh, the less tension exists to push the reader through to the resolution of the plot. There’s another novel, called Off to Be the Wizard, that I recently gave up on for exactly this reason. Even though it was making me laugh more than any piece of fiction I’ve read in quite a while, it was accomplishing that at the expense of trivializing its plot and its characters.

The Martian is able to avoid this problem, and I think that’s because it puts the story first. The laughs come from the protagonist’s believable — and sharp — sense of gallows humor. The comparison I’m making here, by the way, is not exactly fair, because although The Martian can be quite funny, it’s not written primarily for laughs, as is the case with Off to Be The Wizard. The Martian is primarily a novel of human resourcefulness and adaptibility. Second, it is hard science fiction of the most believable kind, filled with facts about astronomy, physics, and botany (yes, on Mars). Funny is perhaps a distant third on the list of things this book is trying to be. But maybe that’s the best way, or at least the safest one, for funny novels to also be good novels. I don’t know.