Yes, I’m aware that I overuse emdashes and parenthetical phrases.

No, I probably won’t stop doing it.

Yes, I’m aware that I overuse emdashes and parenthetical phrases.

No, I probably won’t stop doing it.

Wolf in White Van is a pretty impressive achievement, but it’s difficult to explain why that is without giving away some of what the novel does. I intentionally avoided using the word “spoilers” in that last sentence because, despite what you might think after reading the dust jacket, this is not a plot-driven book. It’s more a portrait of a single character, or a diagram of what makes him tick (though he claims at one point that nothing makes him tick). What distinguishes Wolf from other character-focused books I’ve read, however, is that Sean (the protagonist) is not someone you would normally want to see a portrait of – either literally (he has a horrible facial deformity as the result of a past traumatic event) or figuratively (he is, or at least once was, deeply weird and possibly damaged in ways you will either relate to or not; either way, reading about it is an uncomfortable experience).

I know they’re important but I don’t really like writing them, and since this is my blog I generally won’t unless I feel like I really need to for some reason. If you feel lost without knowing what the book’s basic gist is, I recommend checking the Amazon page, which I try to always link to in my posts. Sorry/thanks!

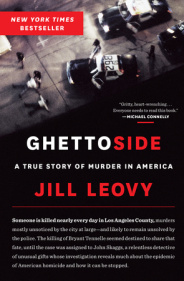

This is essential reading. Frequently, the reason a non-fiction book really grabs my attention is that it relates its thesis convincingly while still managing some how to read like a novel, with fully-formed characters and good pacing. I’m thinking, for example, of Lawrence Wright’s The Looming Tower, which is an absolute masterpiece of journalism on the origins of al-Qaeda, thoroughly sourced and replete with facts, but still as compelling as any thriller. David Grann’s The Lost City of Z, about Percy Fawcett’s ill-fated expedition into the Amazon, is another book with these traits.

Ghettoside is not like either of those books. It’s certainly well-researched and it’s a page-turner in its own way, but the experience of reading it is nothing like the experience of reading a novel. It’s much more like reading a really good, really long newspaper article — which makes sense, because its author was formerly a reporter at The Los Angeles Times. The writing in Ghettoside is fine, but that’s not why you read it, just like that’s not why you read a newspaper article. You read it because the story it tells is important.

I looked it up and “uncouth” comes from old English “uncuth,” meaning unknown (itself from “cunnan,” meaning “to know or be able”). I assume that it gained its current usage by first being used in the sense of “unheard of,” like “What you’re doing is such bad manners it’s unheard of.” I’m just guessing about that, but let’s say I’m right because it makes sense. Nowadays its connotation is not quite that extreme; something uncouth is merely unrefined. It’s funny how words can kind of erode like that, sort of like mountains turn into foothills given enough time. Continue reading

I read a lot of books. On this site, I will write about the ones I like.